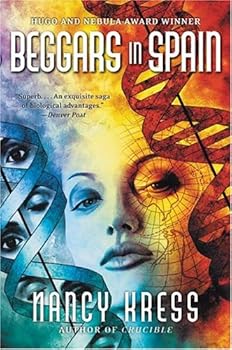

![]() Beggars in Spain by Nancy Kress

Beggars in Spain by Nancy Kress

Nancy Kress won a Nebula and a Hugo in 1991 for her novella “Beggars in Spain,” about genetically altered humans who don’t need to sleep. In 1993 she expanded the novella into a novel and ultimately into a series.

The first quarter of Beggars in Spain is basically the original novella, in which the reader meets Leisha Camden, the genetically altered child of multi-billionaire Roger Camden. Lithe, golden-haired, blue-eyed and beautiful, Leisha is also extraordinarily intelligent and sleepless. How do people feel about Leisha and the others like her, dubbed The Sleepless? The question is more pointed in Leisha’s case — and more personal — because she has a fraternal twin, Alice, who is a Sleeper.

This book is an “idea” book, less about the character and more about how humans, on the individual level, in the aggregate and in the political aggregate, react to changes. Looking at the book twenty years later, it is clear that Kress was spot on in a number of places. Zany laws prohibiting Sleepless from owning 24-hour businesses because they have an unfair advantage do not seem so silly when laws are getting passed now that permit businesses to deny service to couples they think might be gay in the interest of religious freedom. Things that seemed odd-ball and whacky in 1993 do not seem so unbelievable now.

The science behind this alteration takes quite a bit of hand-waving, more so farther into the book when it is revealed that the Sleepless are also going to be quite long-lived, living perhaps for two hundred years without aging. This seems to be done to create more envy on the part of the original humans, and allow Kress to write a book that spans nearly a hundred years with the same characters, but it’s never explained why eliminating sleep would magically cause us to live longer. (I can see the ads for some new energy drink now; “Sleep is killing you!”)

To reduce the legitimacy of some arguments about economic competition, Kress engineers a political and economic USA where everyone’s basic needs are met due to the discovery and exploitation of a new, inexpensive form of energy. Everyone has food and shelter; not everyone has needed medical care or the luxury of meaningful work. Meanwhile, the few hundred Sleepless in the US purchase a tract of land and build their own compound, called Sanctuary, to protect themselves against bigotry and hostility. It’s clear that it is not their wealth that people resent; original humans see the Sleepless as different and different is bad.

Because they are all genetically engineered, which costs money, the Sleepless are all wealthy, all gorgeous and all intelligent. The other interesting thing about them is that, having seven hours a day more original humans, not one of them uses it bar-hopping, skinny-dipping, or looking at cat pictures on the internet. They all seem driven, driven to achieve, at least in the beginning of the book.

For the most part I liked the women characters who populated this book. Leisha is the main character for about the first half. Susan Melling, an original human (a Sleeper, or in pejorative terms, a beggar), is the neuroscientist who discovers how to turn off the need for sleep. Jennifer Sharifi is a Sleepless, the character designed to be a foil for Leisha’s open-mindedness and optimistic acceptance of original humans. Alice is probably the most accessible character, existing as a different kind of foil; an original human, denied her father’s love for something that is not in her control. Alice is One of Us, and her complicated, loving relationship with Leisha adds a much-needed spark to the book.

Leisha herself, however, does not do much after the first quarter of the book. She is driven by the plot rather than driving it, and by the second half she has virtually disappeared. We see her now and then, in her sixties but looking thirty, struggling with the defiant adolescence of her foster son who is a Sleeper. The action moves mostly to the orbital space station that is the new location for Sanctuary, and Jennifer Sharifi, who is striving to engineer even more advanced people.

The last half of the story is told largely from the point of view of Miranda, Jennifer’s “Superbright” granddaughter, growing up on Sanctuary. Kress accomplishes something wonderful with the Superbrights, and that is the metaphor for how they think, in strings. I loved reading the sections where they are communicating with each other, and when they struggle to communicate with the normal Sleepless.

My problem throughout the book was Leisha’s passivity. We know that she edited the Harvard Law Review and passed the bar; she wrote a book on President Lincoln; she confronts a Sleeper who uses hatred of the Sleepless to further his own agenda. However, she does very little else. Basically, she is the one who tells us, the readers, what to think about the bad behavior of the original humans and the increasingly frightening behavior of the Sleepless on Sanctuary. And apparently, nobody in the US government thought that giving control of an orbital platform to a bunch of super-smart techno-scientific types who hate us was a bad idea.

My second problem was the character of Jennifer Sharifi. Jennifer is the daughter of a Hollywood star and a Middle Eastern billionaire, which is odd in itself, since the cheap energy source has made us independent of petroleum. Like all the Sleepless she is beautiful of course. Jennifer has an experience early in the book that cements her disdain for normal humans. She espouses a rigid philosophy that the community is the highest value; that an individual must be productive; and that unproductive people are no longer members of the community. This is one of her rationalizations for her dislike of “beggars;” we only have sixty or seventy productive years and we waste a third of that sleeping. The last half of the book should really test Jennifer’s beliefs, with her granddaughter confronting her, but the scenes with Jennifer and her family-controlled governing council did not read like a woman carrying her ideals to the extreme; they just read like someone with total power acting in a corrupt manner. This is underscored by Miranda’s reaction to her grandmother and her grandmother’s beliefs. Kress falls short of convincing me that Jennifer is deeply sincere in her higher beliefs.

The second problem is smaller, but it bugged me all the way through. Of all the Sleepless we meet in the book, Jennifer is the only one who appears to follow a spiritual belief system. She cites the Quran. She affects the abaya, a traditional Islamic mode of dress, although she never covers her hair. It could be that she looks really good in an abaya, but it’s mentioned nearly every time she appears. No one else has their wardrobe described.

It seems odd that Jennifer, the one who burns with irrational hatred for all original humans, who is a rigid thinker and willing to go extreme lengths to reach her goals, is the only Sleepless with a religious background and that her religion is Islam. Since we see only one snippet of Jennifer’s childhood, which includes an aging starlet mother who is envious of her daughter’s beauty, I never saw why religion, or traditional dress, would be important to her. This makes Jennifer look like a stereotype, and in the long run, weakened the story for me.

Still, there were little moments I really liked. The Sleepless set up a “rescue” network (okay, it’s kind of like kidnapping) for Sleepless children whose original human parents discover they can’t deal with the stress of an infant who never, ever sleeps. Late in the book, the US government, having lost control of the patents for the cheap energy, levies a higher tax level against various companies, and Sanctuary falls into the ninety-two percent category. (Bonjour! Welcome to France.) These things seem plausible given the world created, and realistically written. The depiction of the Superbrights’ mode of communication is beautiful. As I said, this is a book of ideas, and the ideas are ones we are talking about now, today. Beggars in Spain is worth reading for that.

My pleasure, Robin! And yes, it surely is some kind of an experience, to be sure....

Thanks for the solution to a mystery many decades old. One of my favourite novels, this. Hilariously funny, completely unpredictable,…

Thank you. I’m all caught up. Back to reading Crimson Embers.

Enjoyed your review. I’m reading A War in Crimson Embers and am having the hardest time reminding myself where everybody…

Just saw you like Jack Vance. Me too. Surely he offends you somewhere though?