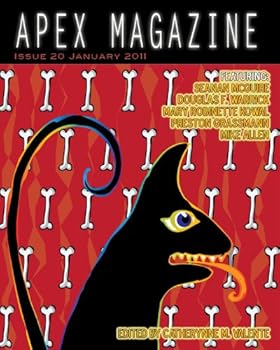

Apex Magazine is an online journal published on the first Monday of every month, edited by Catherynne M. Valente. Valente’s submission guidelines give you a clear idea of what to expect to read within Apex’s pixels: “What we want is sheer, unvarnished awesomeness.… We want stories full of marrow and passion, stories that are twisted, strange, and beautiful.” The January issue definitely meets those requirements.

Apex Magazine is an online journal published on the first Monday of every month, edited by Catherynne M. Valente. Valente’s submission guidelines give you a clear idea of what to expect to read within Apex’s pixels: “What we want is sheer, unvarnished awesomeness.… We want stories full of marrow and passion, stories that are twisted, strange, and beautiful.” The January issue definitely meets those requirements.

“The Itaewon Eschatology Show” by Douglas F. Warrick is a story that cries out to be labeled “New Weird.” It’s about an American in Korea – though why he is there is a complete mystery – who is a “night clown.” This means that every night he, along with his friend Kidu, dresses up and mounts stilts to perform magic for the expatriate crowds in Itaewon. The thing is, they really perform magic; not sleight of hand, no tricks involved, pure magic. At the core of their magic is their ability to show the crowd the End of Days, and they do, every night. What does it mean? Is it a nuclear apocalypse? Is it the attainment of Nirvana? A visit by aliens? A drug that drives us all mad? Read it and decide.

Those who have read Seanan McGuire’s tasty urban fantasies starring October Daye will be surprised at the dark science fiction she serves up in “The Tolling of Pavlov’s Bells.” This excellent story of plague and resistance is as frightening as anything I have ever read, especially because the protagonist – a true anti-hero – has no good reason for what she does except that no one ever listened to her warnings. She is a Cassandra who makes her own predictions of disaster come true. I was unaware that McGuire also writes as Mira Grant, but this story persuaded me that I need to get hold of Feed, the book this 2010 recipient of the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer has written under that name.

Mary Robinette Kowal’s contribution to this issue, “Tomorrow and Tomorrow,” is a complete science fiction murder mystery compressed into about 7500 words. The society Kowal introduces us to is one I would love to see fleshed out into a novel, one where it’s a mark of status to do things by hand, or to hire real humans to do tasks rather than have machines perform them – and the more demeaning the task, the higher the social cachet of paying a human to do it. Tuyet is a professor of philosophy, but she is working as a cleaning woman because that was the only job she could find when she came to Cordova station with her son, hoping to buy him a new pair of lungs. Tuyet’s employers, Cody and Helene, feud constantly, but Cody is a nice man who gives her son massages for free. We never meet Helene, but since she’s the one who seems to work at making Tuyet’s job more difficult, we do not get a good impression of her. It’s a combustible situation, and the explosion, when it comes, is hideous; but the aftermath is even worse.

There are two poems in this issue of Apex, and they are both much better than the usual run of science fiction and fantasy poetry. “The Terminal City” by Preston Grassman is about a city and a sea and a woman, all lost in an apocalypse, all now mere images and imagination. “The Unkindest Kiss” by Mike Allen is a horror poem, a short tale in free verse of a human as a perpetual meal to a monster – which sounds like it should be ugly to read, but it’s beautifully written.

I considered all this a bargain for $2.99 on my Kindle.

The March 2011 issue of Asimov’s Science Fiction is packed with good stories – and I’d warrant there’s a future award winner among them. John Kessel’s “Clean” is one of those stories that makes you feel like your heart is a gong that has just been rung, hard and deep. It’s a story about memory and change, and the choices we make about what is most important to us in life, all in the context of a professor of electrical engineering who is suffering from Alzheimer’s. It seems odd, but the story is never told from the engineer’s point of view, but from his wife’s, his daughter’s and one of the people who is attempting to treat him, so we never feel what he feels directly. That means we never quite understand his decision, any more than his wife and daughter do. It hurts to read this story; it is terribly real even as it proposes a solution not available in our world.

The March 2011 issue of Asimov’s Science Fiction is packed with good stories – and I’d warrant there’s a future award winner among them. John Kessel’s “Clean” is one of those stories that makes you feel like your heart is a gong that has just been rung, hard and deep. It’s a story about memory and change, and the choices we make about what is most important to us in life, all in the context of a professor of electrical engineering who is suffering from Alzheimer’s. It seems odd, but the story is never told from the engineer’s point of view, but from his wife’s, his daughter’s and one of the people who is attempting to treat him, so we never feel what he feels directly. That means we never quite understand his decision, any more than his wife and daughter do. It hurts to read this story; it is terribly real even as it proposes a solution not available in our world.

Another particularly wonderful story in this issue is “Purple” by Robert Reed. Reed proposes the equivalent of an animal shelter for intelligent species, run by a creature than is, for all intents and purposes, a god – just as we are gods to our own pets. This god snatches humans who have been horribly injured and nurses them back to health, returning those who can survive “to the wild.” But those whom the god deems too injured must stay. What does that mean to an intelligent individual? It’s a disturbing story, particularly because it forces us to question the actions of a benevolent god.

Nancy Fulda’s “Movement” is a short story of exceptional power. It is about Hannah, a girl – very nearly a woman – who has temporal autism. I cannot find any indication that such a condition has been identified in our world, but in the context of the story it means that Hannah experiences time differently from the rest of us. Conversations can take weeks in her brain; a question you asked her on January 5 might receive an answer on January 28, but it takes that long for her to choose the right words to answer your inquiry precisely. The real question Hannah must answer is whether she wants to be “cured.” What would she give up if medical personnel started messing about with her brain? Would it be worth the price? And who should make that decision, Hannah or her parents? The stories in this issue all tend to pose difficult questions.

“God in the Sky” is yet another story that poses questions and refuses to answer them. The author, An Owomoyela, gives us a universe in which a light has appeared in the sky about which our astronomers can tell almost nothing except that it is very, very big. They have seen galaxies pass in front of it, so they know that it is incredibly far away despite its brightness. No one knows what will happen, and no one quite knows what to do with herself as the light approaches, even though it is so far off that it will not be “present” in any real way for a very, very long time. This story reminded me of Isaac Asimov’s own “Nightfall,” which famously asked how people would react if they saw the stars only once every several generations.

Ian Creasey plays with the idea of alternate universes in “’I Was Nearly Your Mother.’” The Marian of the universe in which the story takes place lost her mother some time ago – but look, here on the doorstep is her mother from another universe, one in which she aborted the baby that in this universe became Marian. How, exactly, is a teenager supposed to react to a woman who wants to be a replacement for her real, dead mother?

“The Most Important Thing in the World” is a much lighter story by Steve Bein, about a cabbie who finds a passenger has left a time suit behind in his cab. Sometimes the oddest things can change your life, Ernie discovers – both for the worse and for the better.

Nick Wolven’s “Lost in the Memory Palace, I Found You” didn’t work for me. Yet another tale of memory and loss in an age when we’re so bombarded with information that we can’t keep track of it all, the story has a frenetic feel to it that gets in the way of the plot. Neal Barrett, Jr.’s “Where” also seems a lesser story, so dependent on oddity that it forgets to have a plot.

The best science fictional poem I’ve read in a long time is Geoffrey A. Landis’s “The Spirit Rover Longs to Bask in the Sunshine.” If you’ve been following the Mars Rovers the way we have been in my house, you’ve probably personalized them to, at least to some extent. That’s where the poignancy for this poem comes from.

Not sure whether you mentioned it in Twitter, or will mention it tomorrow, but Redwall author Brian Jacques passed away today at age 71.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-merseyside-12380763

He was a major fantasy influence in my early childhood.

Thank you for the sad news, Andrew!

Terry;

This makes me want to download the Kindle app for my PC just so I can get Apex. It sounds wonderful. Thanks for bringing it to my attention.