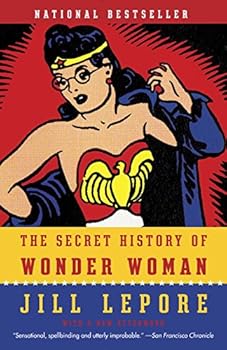

![]() The Secret Life of Wonder Woman by Jill Lepore

The Secret Life of Wonder Woman by Jill Lepore

Jill Lepore has reissued The Secret Life of Wonder Woman, her fascinating non-fiction look at the creator of Wonder Woman, with a revised Afterword that includes information from some new sources. The book is part scholarly work, part Wonder Woman archive and part scandal sheet. Non-fiction is usually pretty slow going for me, but I couldn’t put this book down.

Wonder Woman first appeared in 1941, part of All-Star Comics, a subset of Detective Comics, which was later shortened to DC. In her time she was the third most popular superhero, up there with Superman and Batman. She was a feminist icon, a beacon of strength and hope for young girls. She was a cheerleader of the war effort, encouraging women to join the WAACS and WAVES. She was reviled by critics as anti-feminine, fascist and racist. Her creator, William Moulton Marston, was a feminist who believed women could, should (and would!) rule the world. He was a supporter of women’s suffrage. He claimed to have invented the lie detector, although he is not the person who patented the polygraph. He was also a bondage fetishist.

Suddenly those early Wonder Woman stories (her truth-compelling lariat! Girls in chains!) make a lot more sense.

Suddenly those early Wonder Woman stories (her truth-compelling lariat! Girls in chains!) make a lot more sense.

Lepore delineates Wonder Woman’s connection to the feminist and birth-control pioneer Margaret Sanger, who had a familial connection to Marston. In the early 1900’s young Marston surrounded himself with smart, feminist women like his wife Elizabeth Holloway and Olive Bryne, who was Sanger’s niece.

Marston was born in 1893. He attended Harvard and got a degree in psychology in 1919. At Harvard, he studied with a German professor, Hugo Munsterberg, who became the inspiration for Dr. Psycho in the comics, and during this time Marston advanced a theory that people’s systolic blood pressure changed when they were lying. He developed a technique he began to call the Lie Detector. Marston married his smart, educated childhood sweetheart, Elizabeth Holloway. Marston then went on to be unsuccessful at several things; teaching, law and business were a few examples. Holloway provided the steady income for the family as an editor and writer, working for various magazines and for several years on the updating of the Encyclopedia Britannica. They wanted children, but Holloway wanted to continue working — and they wanted their children raised according to the best and finest psychological theories of the time. When Marston met young Olive Bryne in a college where he was a lecturer, the solution was obvious. Marston, Holloway and Bryne entered into a polyamorous relationship. They raised four children in this arrangement, and when Marston died, Bryne and Holloway remained together until their deaths. The inventor of the “lie detector” and the women around him also lied, thoroughly, to everyone around them, often telling different people a different story, including their children. Marston gave Bryne a pair of wide, heavy silver bracelets that she wore all the time. Wonder Woman fans might recognize them.

Lepore manages to cover this complex and complicated relationship without letting it swamp the book, although I have to say it comes close because this family dynamic was just so weird and fascinating. Lepore gained access to lots of photos and early sketches, but she uses the actual published Wonder Woman work a lot, demonstrating how Marston was influenced by the feminist movement of his early adulthood. Suffragists and feminists often appeared at demonstrations bound and gagged as a symbol of how they were being silenced. Lepore puts cartoons that Marston collected side-by-side with panels from the comic. She points out that Marston, unlike many comics writers, had a lot of control over the artwork, so these similarities are not coincidental. Wonder Woman may have borrowed stories that were “ripped from the headlines” as in The Milk Conspiracy (based on a scandal in California), but the art reached backward for images from suffrage marches and union demonstrations. Who knew Wonder Woman was a union supporter?

Marston, who thought women would lead not from physical dominance but from the “force of love,” and who let a woman support him, did not consider hiring any of the several established women artists working in the comic field in the 1940s to draw Wonder Woman. Lepore points that out without apology or further comment. The chains, ropes and paddles that filled each issue of Wonder Woman did not pass without comment; many community and religious leaders complained, while at the same time, Marston himself got more than one letter from men thanking them for providing pictures of tied-up women, and wondering if the writer knew where they could meet women who would let them do that, or where they could buy the gear. Marston insisted that the chains and ropes were metaphorical. Wonder Woman’s publisher tried to persuade Marston to find other ways to contain the Amazon princess so that the bondage could be reduced “by 50% to 75%” but Marston would have none of it.

In the center of the book Lepore has included a collection of images, largely “Wonder Woman through the decades.” In this section, I discovered that in the sixties, a young science fiction writer named Samuel R. Delaney was hired to write a set of six Wonder Woman scripts. Only one, in which Wonder Woman gets justice for overworked retail clerks at a department store, ever saw the light of day.

There were times when I trouble deciphering Lepore’s sentences, especially when she was discussing the family. This is not Lepore’s fault; names are repeated (William Junior, a daughter also named Olive) and each family member had at least one nickname. For the majority of the book, Lepore’s prose is clear and accessible. To tell this story, she has to address the unique family at its center; two world wars; pre-WWI politics and feminism; the rise of the movie industry; the rise of comic books; academic politics; homophobia; privilege and some deeply rooted values and themes of our country. The book spans eight decades. She did a great job.

Weirder than I imagined, the origins of Wonder Woman are stranger than fiction, and Lepore spotlights them with grace, humanity and a clear, scholarly eye.

Interesting. It sounds like I read the wrong Wonder Woman history with Noah Berlatsky’s book from last year. That was a very dry, very technical read that completely marginalized the character. This sounds like a far more interesting read.

She was willing to look at the personal life and the more sensational aspects of the character’s creator. It isn’t all about him (or more accurately, them) though; she definitely analyzes WW.It was definitely a risk,but it paid off.

I love this book, and I’m glad you liked it — “weird” is a good place to start with Marston.