![]() The Invisibles (Vol. 1): Say You Want a Revolution by Grant Morrison

The Invisibles (Vol. 1): Say You Want a Revolution by Grant Morrison

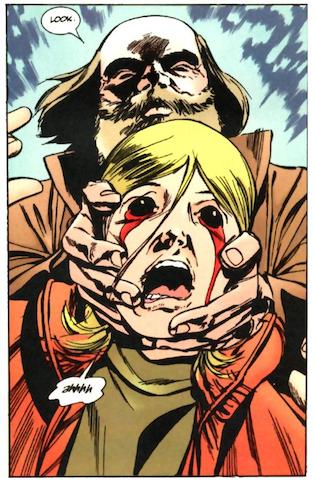

The story in this first volume is about a young, angry, violent teenager named Dane McGowan, who apparently has some supernatural or psychic powers that make him an attractive new recruit for the Invisibles, a team of social misfits who battle the evil forces that go unseen by the majority of human beings. Dane meets the Invisibles through Tom O’Bedlam, an old, destitute man living on streets. Dane, after the first story, is also on the streets, and the apparently loony Tom talks much more sense than Dane recognizes, because insanity becomes sanity in Morrison’s topsy-turvy world. Tom’s real role is to initiate Dane, to take him from the visible London to the invisible one, so that he can meet the team led by K.M., or King Mob, a bald, bright-eyed young man who might be described as punk, and who also certainly resembles Morrison himself. The rest of the team includes Ragged Robin, a young woman dressed as a doll with painted face; Boy, a tough, but kind-hearted woman, who teaches Dane how to fight; and Lord Fanny, a beautiful blonde, kind-hearted transvestite whose sexuality and appearance upset Dane, who is rebellious in only the most superficial of ways at this stage in his life.

The basic message is not original, but that’s Morrison’s point: There always has been and always will be a revolution, and it takes various forms at different stages in history. Sometimes it fails and at other times, it succeeds to a certain extent. But for Morrison, it’s all one long, ongoing battle against those who are powerful and want to control others and make slaves of the bulk of humanity. In different ways throughout these first few issues, he shows the evil force as represented by bankers, religious figures, judges, and royalty (based on a story by the Marquis de Sade, from what I can tell), as economy, religion, the law, and the state all combine the power of the world in the hands of the few to subjugate the rest of us. If this sounds preachy, that’s because it is. If it sounds predictable us-or-them revolutionary art, that’s because it is. If that predictability makes you dismiss it before reading it, then that, from my perspective, proves Morrison’s point: There are invisible forces at work that make it so we can easily dismiss the most revolutionary of ideas. (Though this first volume is fairly black-and-white, the entire series, as far as I understand it, critiques even those who oppose law and order, the Dionysian forces known as The Invisibles; therefore, Morrison’s series as a whole does not stick with this simplistic world-view.)

The basic message is not original, but that’s Morrison’s point: There always has been and always will be a revolution, and it takes various forms at different stages in history. Sometimes it fails and at other times, it succeeds to a certain extent. But for Morrison, it’s all one long, ongoing battle against those who are powerful and want to control others and make slaves of the bulk of humanity. In different ways throughout these first few issues, he shows the evil force as represented by bankers, religious figures, judges, and royalty (based on a story by the Marquis de Sade, from what I can tell), as economy, religion, the law, and the state all combine the power of the world in the hands of the few to subjugate the rest of us. If this sounds preachy, that’s because it is. If it sounds predictable us-or-them revolutionary art, that’s because it is. If that predictability makes you dismiss it before reading it, then that, from my perspective, proves Morrison’s point: There are invisible forces at work that make it so we can easily dismiss the most revolutionary of ideas. (Though this first volume is fairly black-and-white, the entire series, as far as I understand it, critiques even those who oppose law and order, the Dionysian forces known as The Invisibles; therefore, Morrison’s series as a whole does not stick with this simplistic world-view.)

This comic is absolutely genius. It is filled with literary, historical, religious, and cultural allusions that make me dizzy trying to keep track of them all. But Morrison doesn’t throw them in merely to impress or to sound smart. Of the allusions I recognize, they all make perfect sense in the narrative and thematic context of the comic and as a result, suggest to me that Morrison also knows what he’s talking about in the allusions I don’t know. His mind, like Alan Moore’s, is an all-absorbing sponge, and he clearly has an excellent memory that he taps into and combines with creativity. AND he is able to write a story that’s engaging and makes you want to turn the page. It’s not merely weird and unreadable. It’s weird, intelligent, and very readable. I don’t know how he does it.

The Invisibles, at its core, is a coming-of-age story: It’s about a young, rebellious man who is angry for some very good reasons. But it’s also about how he is immature and lacks direction. The Invisibles represent his finding meaning in life, learning to channel his anger and frustration in more positive directions. So far, I find this fairly disturbing book quite optimistic. But why is it disturbing? It features the Marquis de Sade as a main character. The Invisibles travel back in time to meet him and take him into the future, and de Sade is shocked to see people embracing that for which he was condemned in his own time. In other words, there is sex combined with leather, whips, and violence and all the things you might expect. It’s not gratuitous, however. The comic is explicit because it must be to make its point. For Morrison, a transexual is not offensive  but sexual cruelty is. Dane doesn’t seem to be able to separate the two: Both represent sexual perversity to him. I think Morrison is trying to tell his audience that there’s a difference between the two because one is about respecting and caring about other people and the scenes of S&M that we see are the exact opposite. The Invisibles will not appeal to an audience offended by these images no matter what the author’s purpose. The series will also not appeal to those who are not interested in empathizing with a transvestite. None of these aspects of the narrative bother me; they are part of what make the book thematically impressive and positive from my perspective. In other words, if you say you do not want a revolution, then this book is not for you.

but sexual cruelty is. Dane doesn’t seem to be able to separate the two: Both represent sexual perversity to him. I think Morrison is trying to tell his audience that there’s a difference between the two because one is about respecting and caring about other people and the scenes of S&M that we see are the exact opposite. The Invisibles will not appeal to an audience offended by these images no matter what the author’s purpose. The series will also not appeal to those who are not interested in empathizing with a transvestite. None of these aspects of the narrative bother me; they are part of what make the book thematically impressive and positive from my perspective. In other words, if you say you do not want a revolution, then this book is not for you.

We meet and hear about key literary figures who influenced contemporary and future readers to think about oppressive forces. We meet frequently the Romantic poets Byron and Shelley and listen to them discuss the role of art in society. Morrison discusses Kesey and acid and the hippies, but laments through a dehumanized minor character that the promised revolution of the 60s ended as a failure. However, that they are mentioned again in this comic, along with the Romantics, implies that they live on to inspire. Blake, the father of the Romantics, is alluded to frequently as well, primarily through poetic quotation. One of my favorite passages is when Tom O’Bedlam takes Dane into the invisible London through which the polluted Thames still flows. Blake condemned the London in his day as pollution was already building quite visibly from what he called those “dark, satanic mills.” In The Invisibles, Morrison has Urizen, a figure from Blake’s mythology, half-submerged in the polluted river. Mad Tom quotes Blake, “Urizen, deadly black, in chains bound.” For Blake, Urizen represented “your reason,” and was a negative figure bound in chains because man’s reliance on logic and reason to the exclusion of imagination and feelings is what traps us. Blake saw polluted London as an outward manifestation of these inner problems of man.

Urizen is just one example of countless allusions that Morrison employs throughout this page-turner of a comic, and as is clear, he understands fully these allusions and uses them to add thematic depth to his work: The Invisibles thematically represent imagination and emotion and poetry reacting in the exact same way Blake reacted against the visible, reasoned world around him through his own emotion, imagination, and poetry. Once again, it’s all one, long revolution, from Blake to Morrison. As Morrison says in his half-autobiography, half-history of comics, Supergods, he didn’t find meaning in any group until he found the punk aesthetic that he identified not just in the music around him but also in the books he read, like A Clockwork Orange. And Morrison’s early works, and much of his later work as well, is still “punk” in the way he defines it: As revolution against the norm, no matter what form it takes. Kerouac, Ginsberg, The Beats, and The Hippies are punk by this definition, as were Blake, Shelley, and Byron. And Morrison’s The Invisibles was, is, and always will be punk. If you, too, like to find new books, new music, new movies, new art, and any new ideas that are punk, you are going to love The Invisibles: Say You Want a Revolution.

Yikes! I don’t know, Brad. Sounds a little… intense. The artwork does look very 1960s, and that’s a plus with me.

It might not be the series for you. You might prefer one of his other early series: Doom Patrol or Animal Man.

In other Morrison news, his earliest, long out-of-print series Zenith will finally be published in the U.S. starting in Sept. or Oct. and continuing into 2015.

Great review of the first volume of this mind-bending series, Brad. Did you ever read the others?