![]() Some Must Watch by Ethel Lina White

Some Must Watch by Ethel Lina White

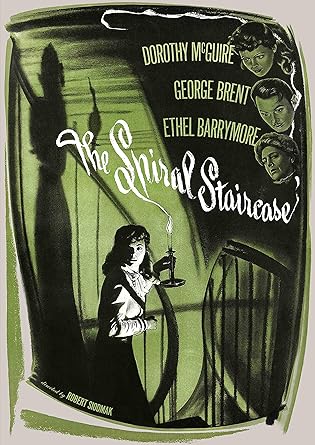

There is a word that film buffs like to use to describe a type of motion picture that, because of its tautness and high suspense quotient, almost seems as if it had been directed by the so-called “Master of Suspense” himself, Alfred Hitchcock. The word, naturally enough, is “Hitchcockian,” a term that might be fairly applied to such wonderful entertainments as Gaslight (both the 1940 and ’44 versions), Charade, The Prize and Arabesque. But of all the pictures that have been honored with the adjective “Hitchcockian” over the years, none, it seems to me, is more deserving than the 1946 RKO film The Spiral Staircase, and indeed, after 40 years’ worth of repeated watches, I have come to deem the picture the greatest horror outing of the 1940s … at least, that wasn’t a product of Universal Studios or producer Val Lewton.

Featuring impeccable direction by Robert Siodmak (his close-up shots of the maniac’s eyeballs in the film are legendary), who would go on to direct the noir classics The Killers and The Dark Mirror that same year; sumptuous set design; and spectacularly gorgeous B&W cinematography by Nicholas Musuraca, who would eventually work on no fewer than five of those Val Lewton horror films, the picture is a genuine classic, beloved by millions. A neo-Gothic suspense thriller starring Dorothy McGuire, giving an almost Oscar-caliber performance despite the fact that she only has three or four lines of dialogue, and abetted by a remarkable supporting cast that is just aces (George Brent, Ethel Barrymore, Kent Smith, Elsa Lanchester, Rhonda Fleming et al.), the picture has been one of this viewer’s personal Top 100 favorites for decades now, and I have long wanted to read its source novel, Welsh author Ethel Lina White’s Some Must Watch. And fortunately, thanks to the fine folks at Arcturus Publishing, a reasonably priced edition can be easily procured today; “fortunately,” I say, seeing that the original hardcover seems to now be completely unobtainable, even on the usually dependable Bookfinder.com website, and the fact that even the 1946 movie tie-in paperback can be a dicey proposition.

White, I should perhaps mention, was a new author for me. Apparently, White began writing somewhat late in life, and her first novel was not released until 1927, when the budding author was already 51. Over the course of 17 years, until her death in 1944, White came out with 17 novels. Some Must Watch, her sixth, was released in 1933. Her ninth, incidentally, entitled The Wheel Spins, was released in 1936 and, two years later, adapted as Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes. Ultimately, White would become known as “The Mistress of Macabre Mystery,” and I suppose that Some Must Watch (an oddly unsatisfying title, for this reader) is a good example of why.

White, I should perhaps mention, was a new author for me. Apparently, White began writing somewhat late in life, and her first novel was not released until 1927, when the budding author was already 51. Over the course of 17 years, until her death in 1944, White came out with 17 novels. Some Must Watch, her sixth, was released in 1933. Her ninth, incidentally, entitled The Wheel Spins, was released in 1936 and, two years later, adapted as Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes. Ultimately, White would become known as “The Mistress of Macabre Mystery,” and I suppose that Some Must Watch (an oddly unsatisfying title, for this reader) is a good example of why.

In the book, the reader meets 19-year-old Helen Capel, who has come to the lonely abode known as the Summit, on the Welsh border, to work as a maid in the service of the Warren family. While there, Helen, a diminutive slip of a girl whose small stature is constantly referred to, gets to know the members of this most unusual household: old Lady Warren, a bedridden, cantankerous invalid who is confined to her room upstairs; her stepson, Prof. Warren, an intellectual cold fish; his prissy sister Blanche; his married son Newton; Newton’s wife, Simone, who is something of a nymphomaniac; Stephen Rice, who the professor is tutoring and whom Simone has set her sights on; and Mr. and Mrs. Oates, two other house servants. Helen seems happy at her new job, despite the loneliness of the locale, and despite the fact that a series of murders has just transpired in the vicinity. Four young girls have recently been strangled to death by an unknown madman, the last incident having occurred only a few miles from the Summit itself. And now, as a monstrous thunderstorm commences one evening, a fifth young woman is strangled almost on the very doorstep of the Warren residence! Some Must Watch takes place during the 12 or so hours following this last murder, as Helen becomes increasingly distraught. One by one, all the residents in the Warren household are rendered unable to assist (the youngsters, caught in their love triangle, take off for the local pub; Mr. Oates is away on an errand; Mrs. Oates is dead drunk; Prof. Warren has taken too many sleeping pills; Blanche is trapped in her room due to a faulty doorknob; the new nurse, Barker, who may or may not be a man, has vanished; Lady Warren is, of course, too infirm to be of aid), until Helen finds herself quite alone, in the middle of a raging storm, with a homicidal lunatic who has somehow found entry into the house…

Longtime fans of Siodmak’s 1946 film may be a bit surprised, after reading White’s source novel, to discover just how many changes screenwriter Mel Dinelli made while adapting the author’s work. For one thing, while the novel is set in contemporary times (in other words, 1933; both King Kong, which had just been released, and Cecil B. DeMille’s 1932 film The Sign of the Cross are mentioned), the film takes place a good 30 years earlier (when we first see Helen in the film, she is watching the silent movie The Kiss, which had been released in 1896), and in New England. The character named Blanche becomes the professor’s secretary in the film; the professor has a stepbrother rather than a sister; and Helen herself, as played by the 5’5” McGuire, is hardly as petite as White had described her. But shockingly, the biggest difference between the book and the film is that whereas Helen in the film is a mute, the result of a traumatic shock at a young age, White’s Helen is anything but … she’s quite the chatterbox, actually! Also, the jealous dynamic between her and Nurse Barker in the novel is excised in the film (Barker, a lonely and unattractive woman, is inordinately envious of Helen being able to enthrall the young Dr. Parry), and the killer’s motivation in the motion picture (that is, the reason why he is compelled to kill physically afflicted women) is completely different, as well. Personally, I find the changes that Dinelli made work marvelously, particularly the idea of having Helen being a mute … most especially since it enables the film to deliver some of the most emotionally affecting closing lines in screen history. So yes, this may very well be one of those rare instances in which the cinematic adaptation eclipses the source material, at least in part. But still, White’s book does have much to offer.

As might be expected, the book is genuinely suspenseful, and it really is remarkable how the author ratchets up her tension slowly, over the course of 250 pages. Every single chapter ends in cliff-hanger fashion, keeping the reader primed for anything that might ensue. During the course of her long, stormy evening, Helen is placed into what the author somewhere refers to as “perpetual postponement;” that is, “nerved up to meet an attack which did not come, but which lurked just around the corner.” The book can fairly be accused of being all buildup, with not enough in the way of payoff, but trust me, although the novel ends a tad abruptly, the threat that Helen girds herself for is a genuine one; a wackadoodle maniac of the first water. My advice would be to not even try to guess the killer’s identity (a simpler guessing game in the movie, I will admit, despite the red herrings), but to just put yourself in Helen’s place (a remarkably well-written and likable character, I must say) and hang on tight.

As would be expected, Some Must Watch is a very British type of novel, employing any number of English expressions (“bally rot,” “dripping toast,” “one over the eight”) and referencing then-popular English entertainers (such as the singer Al Bowlly, as well as bandleader Jack Hylton); yes, using the Interwebs as a recourse here might not be a bad idea. The book is often slyly self-aware, and Helen repeatedly thinks to herself that the situations she finds herself in, such as with the thunderstorm and the cut telephone wires, are like the “faithful accompaniment to the thrill-drama.” White, as it turns out, was a very fine writer, especially when it comes to sharp and witty dialogue, but still, a close reading will reveal some unfortunate gaffes on her part. For example, in one late section, Lady Warren refers to Newton as her nephew, whereas he is in actuality her step-grandson. Her late husband is referred to as Sir Roger in some chapters and Sir Robert in others. The author tells us that Helen was “reliant and conscientious” when she obviously meant to say “reliable,” and shows herself capable of turning an ungrammatical phrase, such as “Helen crossed to the walnut sideboard, where the glass and silver was kept,” instead of “were kept.” Still, quibbles aside, some very impressive and highly atmospheric work here.

During the course of her novel, White shows us Stephen trying to forget his troubles and tension “in the excitement of a thrill-novel,” only to become aware, presently, that “his attention was no longer gripped.” A pity, then, that he did not have a book such as Some Must Watch to flip through, a novel that I personally found quite gripping and almost nerve-wracking (and that’s a good thing!). As a matter of fact, I enjoyed reading this one so much that I now find myself wanting to take in White’s 10th novel, 1937’s The Third Eye, which is supposedly another neo-Gothic thrill ride of sorts. Stay tuned…

I thought “Some Must Watch” was a great title for a “book versus film” review!