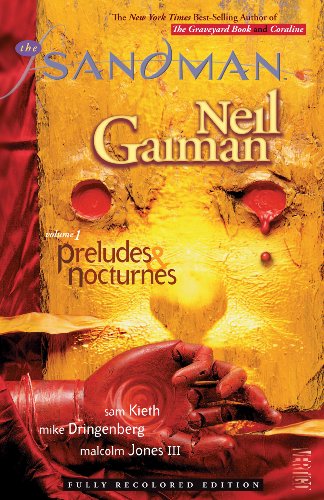

![]() The Sandman (Vol. 1): Preludes and Nocturnes (Issues 1-8): Neil Gaiman (author), Sam Kieth, Mike Dringenberg, and Malcolm Jones III (artists), Todd Klein (letterer), Karen Berger (editor)

The Sandman (Vol. 1): Preludes and Nocturnes (Issues 1-8): Neil Gaiman (author), Sam Kieth, Mike Dringenberg, and Malcolm Jones III (artists), Todd Klein (letterer), Karen Berger (editor)

[This essay is the second in an ongoing series on THE SANDMAN: This lengthy essay-review is for those who want a more thorough introduction than is offered in our shorter overview of the entire series. I recommend reading that one first, particularly since it contains no spoilers and it gives a good sense of what THE SANDMAN is for those who don’t know what it’s about. When I can, I avoid giving spoilers, but I can’t avoid them altogether since I’m going over every story arc in the series. My main goal is to increase the enjoyment of those who want to tackle this masterpiece by calling attention to significant recurring themes, giving information about some of the allusions, and providing any other relevant information that I’ve picked up reading literary criticism of THE SANDMAN and interviews with Neil Gaiman.]

[This essay is the second in an ongoing series on THE SANDMAN: This lengthy essay-review is for those who want a more thorough introduction than is offered in our shorter overview of the entire series. I recommend reading that one first, particularly since it contains no spoilers and it gives a good sense of what THE SANDMAN is for those who don’t know what it’s about. When I can, I avoid giving spoilers, but I can’t avoid them altogether since I’m going over every story arc in the series. My main goal is to increase the enjoyment of those who want to tackle this masterpiece by calling attention to significant recurring themes, giving information about some of the allusions, and providing any other relevant information that I’ve picked up reading literary criticism of THE SANDMAN and interviews with Neil Gaiman.]

Almost anyone who recommends THE SANDMAN will warn that Gaiman’s Preludes and Nocturnes — a collection of the first eight issues — is not representative of, not as good as, the rest of the series. I was given this warning, and I now believe my expectations were much lower than they should have been going into it. It’s a strong start. It’s also essential if you plan on reading the rest of THE SANDMAN.

I think the warning comes out of a fear that a new reader will not move on to volume two on the basis of this first volume. I think that’s a realistic fear. Even Neil Gaiman is hesitant in his praise of these first eight issues. He claims that only in the eighth issue — when Dream’s sister Death makes her first appearance — does he find his own true voice. A good portion of the rest of the issues is imitating a variety of horror stories.

That’s the real fear for somebody like me: That I’ll recommend THE SANDMAN and a new reader will be turned off by some of the horrific stories and images and never move on to the more touching, fantasy-based stories in the series. I’m even willing to suggest someone read this book quickly, flipping through the pages of horror, to get to volume two if the alternative is not reading more of THE SANDMAN at all!

That’s the real fear for somebody like me: That I’ll recommend THE SANDMAN and a new reader will be turned off by some of the horrific stories and images and never move on to the more touching, fantasy-based stories in the series. I’m even willing to suggest someone read this book quickly, flipping through the pages of horror, to get to volume two if the alternative is not reading more of THE SANDMAN at all!

The horror stories, however, are well done, and thanks to THE SANDMAN, I’ve come to appreciate horror stories more than I ever have — other than Poe and Lovecraft, I don’t read horror, and you can’t pay me to watch a horror film. Thanks to THE SANDMAN, however, I now enjoy reading horror titles in comics: THE SWAMP THING, HELLBLAZER, THE WALKING DEAD, LUCIFER (a SANDMAN spin-off), HELLBOY, and comic book adaptations of Poe and Lovecraft. Perhaps you will have the same experience. If you like horror, however, no warning is necessary at all.

To summarize, my advice to new readers is this: If you’ve never enjoyed horror, keep an open mind because you might find — as I did — that you like it in comics; however, if you still don’t like the horror stories in this first volume, don’t give up on THE SANDMAN completely because the entire series is not one long horror story AND the series gets better and better as it goes.

Since I came to comics later than many fans — in my late 30s — I was very nervous about picking up something as monumental and daunting as THE SANDMAN, particularly since it contained horror and references to previous comics with which I was unfamiliar. However, it was one of the first comics I read (after the even more accessible Y: THE LAST MAN), and though I know I missed many comic book references, I still enjoyed the series enough that, based on an initial reading, I was already prepared to consider it one of the best works of art I’d ever experienced! As I’ve reread it in bits and pieces over the past few years, I’ve grown to value and appreciate it even more. But the first step into the world of THE SANDMAN was far easier than I expected.

As you start Preludes and Nocturnes, pay attention to Dave McKean’s wonderful cover art to issue number 1 — It’s the only time that Sandman will be the lead image on the cover of a SANDMAN issue. Also notice that his artwork — often mixing photography with drawing — is very different from the artwork of the story. The story begins with a character being told to wake up, and with Gaiman, there’s almost always a double layer: He seems to have characters speak to each other within the world of the story while those same words have extra meaning for the reader of the comic book. In other words, we, too, are being asked to wake up into the Dreamworld of THE SANDMAN series.

As you start Preludes and Nocturnes, pay attention to Dave McKean’s wonderful cover art to issue number 1 — It’s the only time that Sandman will be the lead image on the cover of a SANDMAN issue. Also notice that his artwork — often mixing photography with drawing — is very different from the artwork of the story. The story begins with a character being told to wake up, and with Gaiman, there’s almost always a double layer: He seems to have characters speak to each other within the world of the story while those same words have extra meaning for the reader of the comic book. In other words, we, too, are being asked to wake up into the Dreamworld of THE SANDMAN series.

Basically, the arc of the first eight issues is an ironic hero’s journey: Dream, or Sandman, is captured on the mortal plane because he’s weak from some previous adventure — an adventure Gaiman has promised to tell us about in a comic book story slated to come out in 2013/2014. The hero of a typical story fights his captors for freedom. In this story Gaiman has Dream sit and wait. And then? He sits and waits some more. That’s it! Sandman does not fight in issue one. He merely waits out his captors until an accident frees him. Only then do we begin to see the power of the King of Dreams. The rest of the story is the human drama of a father and son — each an Alistair Crowley-type Magus — begging Dream to give them power in exchange for his freedom (they had actually attempted to capture his sister Death — so both Dream’s capture and release are accidents).

The background for this story is fascinating: First, Gaiman says, he had to ask himself this hypothetical question: What reason could he invent for readers’ never having read about this Sandman of The Endless in the DC comics Universe? He decided it would have to be because Sandman had been locked away. Then he asked himself how long Sandman would have been trapped. To answer that question, Gaiman turned to an illness in European history and the specific wave of sleeping sickness that passed through Europe in 1916. Gaiman says he decided that Sandman’s capture in 1916, then, would help make sense of this medical phenomenon that to this day has not been explained. Finally, Gaiman decided Sandman must have been help captive for exactly 72 years, or up to late 1988, just when THE SANDMAN comic book series was starting. I love this story of how Gaiman merged comics, folklore, and real medical history into the background of THE SANDMAN. This information is not essential to know to appreciate the comic, but it is representative of the layers that run from issue one to issue 75 of THE SANDMAN. Even when I don’t mention these layers, know that they are there.

The rest of the story arc traces Sandman’s gaining back his three possessions that were stolen from him: His pouch of sand, his Helm, and his ruby (which contains much of his power). He is quite powerless at the moment he is freed and must rely on his wits to gain these items back. Each one presents a unique challenge and takes him on a specific journey in which he usually meets characters from the DC Universe, something Gaiman felt he had to do at the time. Eventually, like Grant Morrison in ANIMAL MAN, he worried less and less about incorporating current DC characters into his series — doing so always leads to editors of the main titles of other main DC characters meddling in the world of THE SANDMAN.

In general, an editor of GREEN LANTERN, for example, must be consulted about current and upcoming GREEN LANTERN story arcs to make sure a writer of another title who wants to use Green Lantern as a walk-on doesn’t use him in a such a way that the consistency of the DCU is violated. I personally believe this practice has probably deprived us of some great artistic stories in the name of continuity, an unnecessary bow to realism in the unrealistic genre of superhero comics. Can you imagine what writers like Grant Morrison, Neil Gaiman, and Alan Moore would have been able to do if given more freedom? Basically, Neil Gaiman’s entire list of initial ideas was shot down by Karen Berger because of continuity and her knowing that Gaiman wouldn’t have creative freedom with certain characters. It’s a very restrictive practice artistically.

As I mentioned already, the first issue, “Sleep of the Just,” is mainly about a Magus who attempts to capture Death and accidentally captures her younger brother, Dream. Gaiman daringly allows his main character to sit still throughout almost the entire issue. By the time the issue closes, of course, Dream gains his freedom; however, he finds himself weak and powerless on the fringes of the Dreamworld from which he is rescued by Cain’s gargoyle and brought to Cain’s house, The House of Mystery (a horror comic series from the 1970s). In this second issue — “Imperfect Hosts” — Cain and Abel take care of “The Prince of Stories” and nurse him back to health so that he can prepare to return to his castle before tracking down the three items that were stolen from him.

As I mentioned already, the first issue, “Sleep of the Just,” is mainly about a Magus who attempts to capture Death and accidentally captures her younger brother, Dream. Gaiman daringly allows his main character to sit still throughout almost the entire issue. By the time the issue closes, of course, Dream gains his freedom; however, he finds himself weak and powerless on the fringes of the Dreamworld from which he is rescued by Cain’s gargoyle and brought to Cain’s house, The House of Mystery (a horror comic series from the 1970s). In this second issue — “Imperfect Hosts” — Cain and Abel take care of “The Prince of Stories” and nurse him back to health so that he can prepare to return to his castle before tracking down the three items that were stolen from him.

“Dream a Little Dream of Me,” the third issue, opens with the morning awakening of John Constantine (the street-wise Magician from the long-running HELLBLAZER series — 300 issues!). He is haunted all day by radios and jukeboxes playing tunes about Dreams and the Sandman before he finally encounters him. Not only is this third issue a great story about how Sandman recovers his pouch of sand, it’s an excellent introduction to the character of Constantine (created by Alan Moore in THE SWAMP THING). The story — as horrific as it is — also has some genuinely funny and tender moments. Constantine’s sarcasm is lost on the dead-serious Dream, who rides around in the back of the taxi while Constantine and his long-time taxi-driver friend Chas sit up front: “John. What do I call him?” asks the wide-eyed Chas. The tender moments, however, are the ones where I can see the mature writer Gaiman showing through. Dream, callous to the plight of Constantine’s dying ex-girlfriend, actually listens to Constantine’s appeals, his pleas for mercy and kindness. And finally, as readers, we’re privy to Constantine, on the final page, actually revealing a personal weakness to Dream and asking a favor of him, one that Dream surprisingly, and kindly, grants.

Issue four, “A Hope in Hell,” is one of my favorite issues in this collection. It’s influenced, according to Gaiman, by the work of such writers as John W. Campbell. For me, the attraction is Sandman’s confronting Lucifer, particularly since Lucifer ends up becoming such an important character that Gaiman will eventually encourage Mike Carey to write an entire series on him. The artwork portraying Lucifer and the hordes of Hell is also perhaps the best so far in the series. It’s stunning. I also have a fondness for the DC character who makes his appearance in this comic: Kirby’s rhyming character Etrigan, the half-man/half-demon servant of Merlin. In this issue, Sandman must retrieve his Helm from a demon by engaging in a public battle of the wits. Obviously, Dream wins, but Gaiman is very clever in how he makes him win. Finally, there’s a second battle of wits that’s perhaps more significant than the first. Lucifer threatens to physically keep him in hell by overpowering him with the help of the gathered demons — Dream’s verbal response is enough to make the demons part and make way for Dream’s walking slowly from Lucifer’s presence (Lucifer, however, vows vengeance).

Issue four, “A Hope in Hell,” is one of my favorite issues in this collection. It’s influenced, according to Gaiman, by the work of such writers as John W. Campbell. For me, the attraction is Sandman’s confronting Lucifer, particularly since Lucifer ends up becoming such an important character that Gaiman will eventually encourage Mike Carey to write an entire series on him. The artwork portraying Lucifer and the hordes of Hell is also perhaps the best so far in the series. It’s stunning. I also have a fondness for the DC character who makes his appearance in this comic: Kirby’s rhyming character Etrigan, the half-man/half-demon servant of Merlin. In this issue, Sandman must retrieve his Helm from a demon by engaging in a public battle of the wits. Obviously, Dream wins, but Gaiman is very clever in how he makes him win. Finally, there’s a second battle of wits that’s perhaps more significant than the first. Lucifer threatens to physically keep him in hell by overpowering him with the help of the gathered demons — Dream’s verbal response is enough to make the demons part and make way for Dream’s walking slowly from Lucifer’s presence (Lucifer, however, vows vengeance).

Issue Five, “Passengers,” is a very odd issue and certainly not the strongest in the volume: It’s odd because Gaiman manages to show us a large number of DC characters that seem out-of-place. Martian Manhunter, Doctor Destiny, Scarecrow, Granny Goodness, and Scott Free (Mister Miracle) all show up in the issue. Gaiman says that he was continuing to try to show how his series fit into the larger DC universe. Karen Berger felt that it helped bring in readers, but reading it years later, I find it to be a very awkward issue. My favorite aspect of Gaiman’s including Martian Manhunter is that we can see that Dream appears much differently to him than to Scott Free (and us) and has a different name. Gaiman allows us to see, as he does in the previous issue when Dream is seen by an old lover in hell  (Nada, whose story is told in issue #9), that Sandman changes appearance and name based on time and culture and, in the case of Martian Manhunter, even based on planet! Arkham Asylum also figures in prominently as Doctor Destiny escapes, but largely this issue is a set-up for the very disturbing issue number six.

(Nada, whose story is told in issue #9), that Sandman changes appearance and name based on time and culture and, in the case of Martian Manhunter, even based on planet! Arkham Asylum also figures in prominently as Doctor Destiny escapes, but largely this issue is a set-up for the very disturbing issue number six.

“24 Hours,” Gaiman says, lost a large number of readers at the time it came out. It’s a horrific portrayal of a diner full of people being tortured to death within 24 hours. And yes, it’s as pleasant as it sounds. Gaiman says that after this issue, many people “didn’t come back [to reading THE SANDMAN] for ages, until they were told it was safe.” It is certainly not my favorite story because of how gruesome it is; on the other hand, it’s thematically significant. Gaiman says it was the first time he realized he was “writing a story about stories.” Because the horror is most memorable, it’s easy to overlook that the issue starts out making clear that the waitress is a writer. This level of meta-narrative runs throughout the series and is one that greatly appeals to me. It’s an interest that runs through much of Gaiman’s work after Sandman as well. I often like to have something to look for when reading a writer — often a writer’s main obsession like PKD’s about “the real” and “the human” — and I think any new reader of Gaiman’s could use this motif of interlocking stories as a handhold, or guide, into the world of Neil Gaiman. This issue also introduces explicitly a theme that Gaiman claims is central to the entire series, a theme that appropriately makes a claim about story-telling: “You get happy endings only by stopping at a certain point.” Otherwise, as we all know too well when we stop to think about it, all stories end in death.

“Sound and Fury,” the second-to-last issue in the collection, wraps up the first story arc: Having gained his pouch with the help of Constantine and having won back his Helm through a descent into Hell, Dream once again has his ruby returned to him, but with a difference. He faces off with Doctor Destiny and wins by accident, almost surprised by victory.

This arc is largely a warm-up act — Gaiman claims he named the collection Preludes and Nocturnes because he felt they were introductory exercises to prepare him for the main event, the rest of THE SANDMAN. However, key characters and themes are introduced. They prepare the reader for what is to come. Gaiman, for all his mere practicing, certainly seems to have known where he was going with the series, particularly in terms of his main character: Sandman, even though he’s a personified entity, seems to slowly change as the arc progresses. He seeks revenge at the end of issue one, punishing the son of the man who captured him. But in the issue with Constantine, when prompted, Dream is able to act kindly, and by the time he defeats Doctor Destiny, he is capable not only of returning him to Arkham Asylum but also of allowing him to sleep peacefully. In fact, Dream brings peaceful sleep to all of Arkham Asylum for one much-needed respite.

Gaiman has talked much about the unusual nature of Dream and the rest of The Endless. Dream is the main character of his series, but he’s not a typical fictional hero or main character who is capable of epiphany or change, or at least he SHOULDN’T be: “As personifications of things, they’re not causative,” Gaiman says of The Endless. “They’re barely reactive.” So we should pay careful attention when Dream, who at the beginning of the series is exactly as Gaiman describes, starts to change and have realizations. What is Gaiman telling us when a mythic, eternal figure changes? Even Hell has undergone a change, we are told. And what happened to the AWOL member of the Endless? What happened to humanity and the nature of reality in the 20th century that Eternal beings have begun to change? And why does he insist that the Endless are NOT gods because gods can die at the whim of their believers and The Endless outlive all gods? I believe these are key questions that Gaiman wants us to ask ourselves as we read his thought-provoking series.

Preludes and Nocturnes ends with “The Sound of Her Wings,” an issue that most agree is where the Sandman series takes off and Gaiman finds his voice as a writer. It’s also the issue in which Dream’s older sister Death makes her first appearance. Almost nothing happens in terms of action, but it’s a story with heart as we listen to Dream complain to his sister while he feeds the birds. Dream is the Byronic hero, but Death finds his brooding ridiculous. After trying and failing to cheer him up by quoting Mary Poppins, she finally hits him over the head with a loaf of bread and yells at him in a character-defining moment: “You are utterly the stupidest, most self-centered, appallingest excuse for an anthropomorphic personification on this or any other plane! An infantile, adolescent, pathetic specimen! Feeling sorry for yourself because your little game is over, and you haven’t got the — the BALLS to go and find a new one!” This lecture from his older sister is delivered with real passion, yes, but also out of real love, we sense. And so, the rest of the issue is merely Dream’s taking the time to follow around his big sister — who is nothing like the Grim Reaper — as she performs her duties with incredible kindness.

Preludes and Nocturnes ends with “The Sound of Her Wings,” an issue that most agree is where the Sandman series takes off and Gaiman finds his voice as a writer. It’s also the issue in which Dream’s older sister Death makes her first appearance. Almost nothing happens in terms of action, but it’s a story with heart as we listen to Dream complain to his sister while he feeds the birds. Dream is the Byronic hero, but Death finds his brooding ridiculous. After trying and failing to cheer him up by quoting Mary Poppins, she finally hits him over the head with a loaf of bread and yells at him in a character-defining moment: “You are utterly the stupidest, most self-centered, appallingest excuse for an anthropomorphic personification on this or any other plane! An infantile, adolescent, pathetic specimen! Feeling sorry for yourself because your little game is over, and you haven’t got the — the BALLS to go and find a new one!” This lecture from his older sister is delivered with real passion, yes, but also out of real love, we sense. And so, the rest of the issue is merely Dream’s taking the time to follow around his big sister — who is nothing like the Grim Reaper — as she performs her duties with incredible kindness.

In the end, surprisingly, Sandman does have an epiphany, his acknowledgment of what he has learned from his sister. Gaiman’s writing — as it always is at its best — is poetry in prose: “My sister has a function to perform, even as I do. The Endless have their responsibilities. I have responsibilities. I walk by her side, and the darkness lifts from my soul. I walk with her; and I hear the gentle beating of mighty wings . . . ”

I’ll leave you with those final words from Sandman in the hopes that you’ll remember them instead of some of the other scenes I mentioned. Though Gaiman often employs elements of Horror, those elements are used to heighten our sense of the sublime present in our everyday lives. The risk, the danger, the Nightmares, Gaiman seems to tell us, make us appreciate all the more the beautiful dreams when they finally come to us or when we drift off into them. Sandman awaits and perhaps even beckons.

~Brad Hawley

![]() Neil Gaiman’s THE SANDMAN is such a legendary comic series that it needs no introduction at this point. It ran from 1989 to 1996 as the flagship series for DC imprint Vertigo Comics, indicating a shift to more mature content. This came shortly after the arrival of Alan Moore’s Watchmen (1986) and Frank Miller’s Batman: Dark Knight Returns (1986), heralding a renaissance in the comic book industry. No longer were writers satisfied with superheroes knocking out super villains with visual sound-effects like “Ka-pow!” Comics were being aimed at adults who wanted more sophisticated content, often with darker themes.

Neil Gaiman’s THE SANDMAN is such a legendary comic series that it needs no introduction at this point. It ran from 1989 to 1996 as the flagship series for DC imprint Vertigo Comics, indicating a shift to more mature content. This came shortly after the arrival of Alan Moore’s Watchmen (1986) and Frank Miller’s Batman: Dark Knight Returns (1986), heralding a renaissance in the comic book industry. No longer were writers satisfied with superheroes knocking out super villains with visual sound-effects like “Ka-pow!” Comics were being aimed at adults who wanted more sophisticated content, often with darker themes.

Over the last year, I’ve been re-introducing myself to comics (or ‘graphic novels’ as they are often called) after a hiatus of 30 years or so. Once I got into SF and fantasy novels, both comics and RPGs quietly got left behind. I don’t remember it being a conscious decision, I simply was so engaged with books that I wanted to dedicate all my reading time to them. And so ground-breaking titles like SANDMAN and Watchmen were only in the periphery of my attention. But ever since joining Fantasy Literature, I’ve been reading fellow reviewer Brad Hawley’s gushing praise of comics and exhortations to give them a chance, particularly people like me who love the SF/fantasy genre but have ignored comics for years. Check out his essays Why You Should Read Comics: A Manifesto! and the 10-part series Reading Comics and you’ll be convinced you’ve been missing out. Since the start of the year, I’ve read Watchmen, V for Vendetta, Batman: Dark Knight Returns, Batman: Year One, SAGA, SIN CITY, and now SANDMAN.

Brad has written comprehensive reviews on the individual SANDMAN titles, as well as an intro to the overall SANDMAN series (click here), so I will not rehash the details. Suffice to say Vol 1 is a fascinating introduction to the world of Morpheus (also known as Dream or the Sandman), one of The Endless (the others including Destiny, Desire, Despair, Delirium, Death, and one missing member). Morpheus is closest with his older sister Death, and both have a strong Goth look, much like members of Flock of Seagulls or Robert Smith from The Cure. Pale white faces, big spiky hair, and all-black wardrobes. And sister Death has a very quirky sense of humor as she gently harvests souls both young and old, happy and sad.

Vol 1 begins with Death in a very weakened state, trapped by mere mortals who wish to tap his powers for their own purposes. He is held against his will for 70 years, and is separated with three objects that contain much of his power and vitality — his Pouch, Helm, and Ruby. Much of the book is occupied with Morpheus tracking down these items, each time having to overcome greater obstacles and opposition. In addition, his kingdom, The Dreaming, has fallen into chaos in his absence. His adventures returning to his dream world, descending into Hell, and fighting a powerful villain in a 24-hour diner, are both unique and disturbing, and Dream behaves very differently from what I would have imagined of an immortal being.

The storylines, artwork, and dialogue are also wonderfully integrated. Gaiman has pioneered a very unique approach to visual storytelling, incorporating elements of myth, history, fantasy, horror, and understated humor as well. This initial volume also features a lot of DC universe characters that the author initially felt were necessary to the story, but with future volumes this diminishes as he finds his own voice. So some readers might be a bit confused, especially those like me who are not really familiar with the DC universe. However, having read the next few volumes, I would advise not worrying about it too much – they are not crucial to the overarching storyline. And as Brad pointed out, this volume also has some pretty gruesome horror in the 24-hour diner sequence which may upset some readers, but hopefully you can get through that since it is less prominent as the series progresses.

I read the first three volumes before deciding that I needed to re-read Vol 1 to really appreciate the details and foreshadowing of events. Once you get to know the world Gaiman has created, you can really grasp what a complex tapestry he is weaving, which will only be fully revealed in the 10-volume, 76-issue series, plus several side volumes and a prequel. I have enjoyed reading it in e-format on Comixology, allowing me to read in anywhere on the PC, iPad, and iPhone. Guided View allows you to go frame by frame, making it a different experience from reading a print copy, but also very flexible. ~Stuart Starosta

I’m glad to read this review. It’s inspired me to go back and reread the run after having it put away in a box for almost 10 years (that’s not as long as it used to be, however).

I’m suspecting I’ll actually like this arc better than the ones to follow. For some reason, Gaiman’s poetic streak doesn’t appeal to me a lot right now. I’m thinking the clumsy and the horrific will be just the thing.

that’s exactly what I was thinking. though i suspect A Game of You will have that right mixture of horrific and clumsy.

Greg, that’s interesting that the poetry of his writing is less appealing than the horror elements. I’m surprised, but I’m starting to understand the appeal. However, I’m still struggling to understand why the horror genre that is virtually impossible for me to watch on screen (even in silly light-weight horror TV shows) is somewhat mystical and magical and intriguing to me when I see it in a comic.

I feel this same way, Brad. I CAN NOT watch horror on the screen. I even have trouble with crime dramas or anything that has bad things happening to people, especially children. I can, however, READ about it, and it doesn’t bother me in comics even though that’s still a visual format.

Great series and great article. I read an interview with Alan Moore where he claimed that DC comics were so dearth of new ideas that they basically invented a new line to copy Watchmen (Vertigo). although i’m sure Alan is an admirer of Gaiman, what he said was out of anger for the situation involving DC’s Watchmen. Sandman is proof that the Vertigo line was not a one trick pony and could move AFTER Watchmen. I have very fond memories of waiting each month for my subscription to be filled at the comic store for Sandman. Now I have to go back and reread those old issues again!

Thank you, Jay!

I think Moore has some excellent reasons for being angry, but I’m also angry at him for not figuring out a way to work with DC. Of course, if I’d been the president at DC or Marvel, I’d just tell him that he’d get good royalties AND he could have his own DC Alan Moore Elseworld to play in. With no limits on what characters he used our what he made them do. Complete artistic freedom with Vertigo label for adult audiences and freedom of language and content. DC would make a bundle because everybody would have bought Moore creating in excitement, at the height of his creative powers. And even though they told Gaiman NO about using a bunch of characters, why, after SANDMAN, didn’t they BEG him to use any and all the characters HE wanted in any artistic manner? Can you imagine how many more cool comics we’d have today?!

However, as you say, I think Berger, Vertigo, and all those writers who worked for Vertigo proved that Moore paved the way, but he wasn’t a lone voice.

I don’t read many comics, so sometimes I feel like I don’t “get” everything. Therefore, I’m looking forward to reading SANDMAN with your reviews as a guide. I’ve read some of this first volume, but not further yet. I’ll do a re-read of Vol 1 and try to keep up as you review the others. Thanks!

I’ve wondered about the whole read it/can’t watch it thing. I think that even with graphic novels there is a degree of psychic distance. Now I’m going to contradict that. The things that stay with me and disturb my sleep are usually things I’ve read, not things I’ve watched.

Have you seen the cover for the first issue of the prequel? http://io9.com/first-glimpse-of-the-cover-of-neil-gaimans-new-sandman-633658776