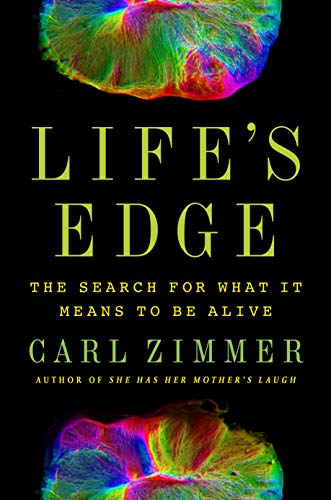

![]() Life’s Edge: Searching for What It Means to be Alive by Carl Zimmer

Life’s Edge: Searching for What It Means to be Alive by Carl Zimmer

In the past year alone, humans have landed multiple devices on Mars, retrieved samples from the Moon and not one but two asteroids, delved ever deeper into the Earth, and shattered records for the recovery of DNA from ever-older specimens. Meanwhile, plans are being hatched to zip a helicopter around Titan to examine its pools of liquid hydrocarbons, fly a probe through the geysers of Enceladus to collect samples, scoop surface ice off Europa, and use the next generation of space telescope to examine the atmospheres of exoplanets light-years away. All in the search for life.

In the past year alone, humans have landed multiple devices on Mars, retrieved samples from the Moon and not one but two asteroids, delved ever deeper into the Earth, and shattered records for the recovery of DNA from ever-older specimens. Meanwhile, plans are being hatched to zip a helicopter around Titan to examine its pools of liquid hydrocarbons, fly a probe through the geysers of Enceladus to collect samples, scoop surface ice off Europa, and use the next generation of space telescope to examine the atmospheres of exoplanets light-years away. All in the search for life.

Given all that time, effort, and money, one could be forgiven for assuming that we know what we’re looking for. But, as Carl Zimmer makes explicitly clear in his newest popular science work, Life’s Edge: Searching for What It Means to be Alive (2021), that’s not even close to reality.

Turns out we not only don’t know the meaning of life (OK, 42); we don’t even know what it means to be alive. To try and circle around the question, if not arrive at an actual answer, Zimmer has penned a series of linked essays that explore various aspects of the mystery and the many attempts, historical and contemporary, to solve it through various means: chemistry, biology, physics, philosophy, astronomy.

He travels to a mine in the Adirondack Mountains of NY to count hibernating bats, to laboratories to watch slime molds find the shortest path to food, to a New England Arboretum to learn how maples reproduce, to the Jet Propulsion Lab to interview astrobiologists about NASA’s search for life. He explores the long-running medical problem of when to declare someone dead — Is it when the heart stops? The lungs? Brain activity? — as well as the just as long debate between vitalists, who believed in a “vital force that endowed matter with self-directed motion [and] purpose, and Cartesians and their “machine-centered view of life … seeing themselves in league with clock repairman.” And finally he ends just where one might expect in a book that begins with questions of how life began — in several labs trying to create life anew.

Along the way we get some familiar definitional parameters: life has to reproduce, life has to metabolize (eat and turn that food into energy), life has to evolve, and others. And just as quickly as Zimmer offers up these requirements, he shows us the exceptions or at least the boundary-blurrers, such as computer programs that evolve in self-directed manner and tardigrades that enter a weird no-person’s land between life and death (here you might ponder the thought that tardigrades might even now be living on the Moon, thanks to a crashed probe).

It’s all endlessly fascinating, not in spite of life’s ambiguities and contradictions, but because of them. Zimmer doesn’t appear to have any leanings one way or the other on the various theories, at least not one that shows, but what shines throughout Life’s Edge is his curiosity and his desire to explore all nooks and crannies, including not just scientists but also writers and philosophers. Nor does he highlight only the “successes,” since science advances as much via what some might call its “failures” (or at least errors), which Zimmer treats with the same respect as he does those theories that have better withstood the test of time. Meanwhile, his prose is always clear and smooth, and his explanations never get bogged down in too much detail or complexity. Sometimes a few of the sections feel like they end a bit abruptly, or the linkages could be a little smoother, but these were niggling issues in an otherwise informative and fascinating work. In the end, you won’t have an answer to, “What is Life,” but you’ll be exhilarated at the journey to find out.

It’s all endlessly fascinating, not in spite of life’s ambiguities and contradictions, but because of them. Zimmer doesn’t appear to have any leanings one way or the other on the various theories, at least not one that shows, but what shines throughout Life’s Edge is his curiosity and his desire to explore all nooks and crannies, including not just scientists but also writers and philosophers. Nor does he highlight only the “successes,” since science advances as much via what some might call its “failures” (or at least errors), which Zimmer treats with the same respect as he does those theories that have better withstood the test of time. Meanwhile, his prose is always clear and smooth, and his explanations never get bogged down in too much detail or complexity. Sometimes a few of the sections feel like they end a bit abruptly, or the linkages could be a little smoother, but these were niggling issues in an otherwise informative and fascinating work. In the end, you won’t have an answer to, “What is Life,” but you’ll be exhilarated at the journey to find out.

Just saw you like Jack Vance. Me too. Surely he offends you somewhere though?

Words fail. I can't imagine what else might offend you. Great series, bizarre and ridiculous review. Especially the 'Nazi sympathizer'…

"Nor Iron Bars a Cage by Kage Harper" Freudian slip there. ;)

[…] (Fantasy Literature): In 1957, Hammer Studios in England came out with the first of their full-color horror creations, […]

I'm going to have to find these and read them.