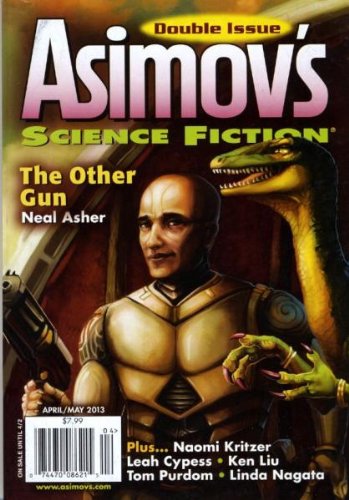

The April/May 2013 issue of Asimov’s leads off with a difficult but exciting novella by Neal Asher entitled “The Other Gun.” It portrays a complicated universe in which humanity has found itself at war with a race called the prador, which is ruthless, merciless and completely uninterested in compromise. It has already exterminated several species when it runs into humans, and a survivor of one of those wars, a member of a hive species, has allied itself with humans. The narrator of this tale is a parasitologist and bio-synthesist who was working on a biological weapon to be used against the prador when he was reassigned to work for the Client, as he knows the survivor of another species. The Client has somehow managed to steal a prador cargo ship, and is using it to hunt down pieces of a doomsday weapon called a farcaster that had been broken up and scattered across the galaxy. The narrator no longer has a human body in any sense that we would recognize as such; his only companion, other than the Client (which isn’t a companion or company to the narrator, but more of a master, with the narrator as his slave) is a heavily modified human woman who now has the appearance of a small dinosaur; think of the raptors from Jurassic Park. As the story progresses, following the narrator through years of travels searching for pieces of the farcaster (though the years move more quickly for us than for the narrator because of time dilation from faster-than-light travel), we learn more about the technology of the war and the purpose of the Client, as well as the purpose of the narrator. It’s a horrifying tale in the way that a war story is horrifying, made more so by the advanced technology in use. I’m looking forward to reading Asher’s books set in this universe, as well as his new trilogy set elsewhere, starting with The Departure, which has just been issued by Night Shade Books.

The April/May 2013 issue of Asimov’s leads off with a difficult but exciting novella by Neal Asher entitled “The Other Gun.” It portrays a complicated universe in which humanity has found itself at war with a race called the prador, which is ruthless, merciless and completely uninterested in compromise. It has already exterminated several species when it runs into humans, and a survivor of one of those wars, a member of a hive species, has allied itself with humans. The narrator of this tale is a parasitologist and bio-synthesist who was working on a biological weapon to be used against the prador when he was reassigned to work for the Client, as he knows the survivor of another species. The Client has somehow managed to steal a prador cargo ship, and is using it to hunt down pieces of a doomsday weapon called a farcaster that had been broken up and scattered across the galaxy. The narrator no longer has a human body in any sense that we would recognize as such; his only companion, other than the Client (which isn’t a companion or company to the narrator, but more of a master, with the narrator as his slave) is a heavily modified human woman who now has the appearance of a small dinosaur; think of the raptors from Jurassic Park. As the story progresses, following the narrator through years of travels searching for pieces of the farcaster (though the years move more quickly for us than for the narrator because of time dilation from faster-than-light travel), we learn more about the technology of the war and the purpose of the Client, as well as the purpose of the narrator. It’s a horrifying tale in the way that a war story is horrifying, made more so by the advanced technology in use. I’m looking forward to reading Asher’s books set in this universe, as well as his new trilogy set elsewhere, starting with The Departure, which has just been issued by Night Shade Books.

“Through Your Eyes” by Linda Nagata is about how some police, and some politicians, think that they can do whatever they please when no one is watching. But technology will always find a way to watch. I’m reminded of recent court decisions throwing out laws that prohibit the videotaping of police as they go about their business. The story is short, but thoroughly effective.

Joel Richards’s “Writing in the Margins” portrays a world that knows, for a scientific fact, that humans are reincarnated after their deaths. In this world, Tim Marchese is attempting to keep his wife, Marilee North, alive after an accident has left her a paraplegic. Her former life as an aerobics instructor and personal trainer is severely changed, even though she is still an athlete in any sport that requires upper body strength and still able to provide the best personal training. Why should she stay alive when she could commit suicide and hope for a better life next time around? This isn’t the sole plot of this thought-provoking novelette, though. Tim is a homicide detective, and his work has also been changed by the new understanding of lives, past lives and future lives. It is possible, though just barely, to actually recollect one’s past life. In fact, sometimes those recollections will trouble a child who cannot understand or process what he or she is remembering. As Tim works to solve an older crime with the help of such a recollection, many issues of justice and mercy arise. For instance, a death sentence is now considered the merciful way to treat a violent criminal, while life in prison is sentencing one to decades of torture instead of letting the prisoner move on. It’s a fascinating story that you won’t soon forget.

Karl Bunker’s “Gray Wings” posits a world in which some people are literally rich enough to grow wings (or at least have them grafted) that will allow them to fly without the aid of any mechanism save their own muscles. In the same world, some people are so poor that they don’t have enough to eat. What happens when a flyer crash lands into and through the roof of a barn of a family living in dire poverty? Does it give the poor young man who runs to help the flyer something to dream about? Does it give the flyer a twinge of conscience? A thoughtful reader is likely to come away with many more questions about those who have more than enough in a world where others haven’t enough to keep body and soul together.

“Julian of Earth” by Colin P. Davies is great fun to read. Tarn Erstbauer is a young man who makes his living — barely — by showing offworlders around the jungle that surrounds the home he shares with his mother. He trades on a story of his abduction as a child by Julian, a legendary soldier who organized raids from the center of a jungle the settlers never penetrated with the help of the native species, the primes. One day a small group of tourists arrives, promising riches to Tarn if he will help them find Julian and film the search for a documentary. All of them find much more than they were looking for. The story isn’t particularly original, but it is enjoyable.

“The Wall” is a new take on time travel by Naomi Kritzer. In February 1989, Maggie, a college student, is greeted in the student center by a woman who looks like her mother. The woman says she is a future Maggie, and urges the 1989 Maggie to go to Berlin to study abroad the next fall. The reason? The Berlin Wall is going to fall on November 9. The 1989 Maggie now knows that this is clearly a joke, and tells her supposed future self to get lost because she has to finish her calculus homework. Future Maggie tells her she’s going to get a D and should just drop the course. And so they’re off! There are plenty of future confrontations between the two of them, but their pasts start to look different; for instance, 1989 Maggie decides to get some tutoring for calculus — something future Maggie never thought to do — and gets a B+. But future Maggie, who goes by Meg, continues to hector Maggie about getting to Berlin. It’s fun to read, and it made me wonder what I’d tell myself if I could go back to visit me when I was in college. Talk about alternate universes!

I’ve always liked mash-ups between mysteries and science fiction, so Alan Wall’s “Spider God and the Periodic Table” was a treat. It’s hard to play fair when you’ve got scientific advances unheard of by your readers to play with, but Wall manages. The story begins with a doctor reporting on the autopsy of a body in which a radiating force crystallized the area of the brain immediately above the brainstem, leaving the neocortex, where higher brain functions occur, untouched. What could cause this strange effect? Pretty soon we’re not only deep into neuroscience, but into the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas.

“Distant Like the Stars” by Leah Cypess is about an effect of instant place-to-place travel I’d not considered: it might make some people claustrophobic. When there’s no longer any real distance, when it is no longer possible to get truly away, the universe might seem to close in around someone like the narrator of this tale. She travels to a distant planetary system with a group of hardy folks who plan to tame an untamed world all by themselves, with no possibility of going back. For Sylvana, this is the only type of distance that really means anything to her. But technology has a way of advancing, and soon instantaneous transport reaches even Sylvana’s distant planet. She plans to destroy it. It’s what happens from there that comprises the heart of this intriguing story.

Ken Liu has been writing one magnificent story after another lately, and “The Oracle” now joins his portfolio. This take-off on Philip K. Dick’s “Minority Report” is about Penn, a man who is a pre-criminal, housed in a genteel prison for the past 20 years, since he was 19 years old. The Oracle had foretold that he would be legally executed at some point, presumably because he murders someone. He therefore hasn’t been allowed to live his life, which makes him so angry that he believes he probably is capable of a crime worthy of the death penalty. One day a woman who is a mitigation specialist with the No Pre-Judgment Project shows up at the penal farm where he gardens. The meeting is fateful, but not necessarily in the way you might imagine from that setup. Consistent with the philosophical tone set in this issue, the questions of free will and predestination consume the story without turning it preachy. It’s a difficult line to tread, but Liu does it.

Interspecies war is Tom Purdom’s subject in “Warlord.” It’s mostly a straight adventure story of the interactions of three species in a fight for territory, but the strategies and, yes, the philosophy of war are entertaining to read. I especially liked that Purdom’s hero isn’t a Conan type, but a nearsighted man who gets most of his advantage from his brain, not his brawn.

This issue is stuffed with poetry. I’m coming to think of Geoffrey A. Landis as a very fine poet, an impression that is confirmed by “On the Semileptonic Decay of Mesons.” You’d never guess from the title that this poem mourns a lost love, but it does, and beautifully. “Maintenance Subroutine: Sanity” by Robert Frazier is also a poem about a lost love, but is less successful. William John Watkins’s “Indefensible Disclosures” is a metapoem, so to speak, a poem about poetry, and the fancy of poetry as a disease works surprisingly well. “Sunday at the Quantum Revival” by Danny Adams wants to be about the conflict between religion and science, but it doesn’t manage to say anything new. “Out of My Price Range” by David C. Kopaska-Merkel doesn’t fall together; it’s too short to make the sophisticated argument it seems to want to make. I liked “Shadow” by Igor Teper, which is aimed at the philosophical questions that make up much of this issue. Sara Backer’s “The Potion” poses a nice problem for the protagonist, dwelling on the “if” that makes decisions so difficult.

A few nonfiction pieces round out the issue: Norman Spinrad on books, Sheila Williams on spaceflight, and particularly on women as astronauts; James Patrick Kelly on SF editors. Robert Silverberg writes about his desk, making me wonder whether he’s become completely bereft of ideas, but it’s the only true clunker in an otherwise excellent issue.

Hi Terry, and thanks for the review. I have to add that The Departure and ensuing books are not set in this universe. However, most of the books below those here are: http://freespace.virgin.net/n.asher/page3.html

Oops. I must have misread Asimov’s intro to the story. I’ll correct the review — and please accept my apology.